In Michigan our broadleaved trees shed their leaves every autumn and most of our conifers hold their leaves (needles) for multiple years. All of our broadleaved trees are true flowering plants also known as angiosperms. Our conifers are non-flowering plants called gymnosperms. They have pollen cones and seed cones that technically are not flowers.

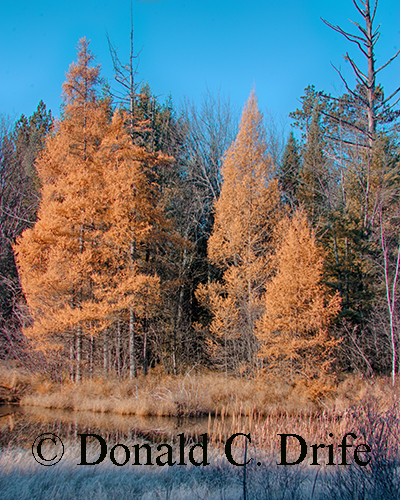

Tamarack is our only native conifer that drops its needles for the winter. Our other conifers do not hold their needles forever but shed some each year, normally in autumn. White and Jack Pines hold needles for two years, Red Pines four to five years, White and Black Spruces, and Balsam Fir seven to ten years. Evergreens photosynthesize year round. Their needles have a waxy coating called the cuticle which slows down water loss. Evergreens are also less tasty to predators than broadleaved trees. Evergreens tend to have an upright growth making them less likely to get damaged by accumulating snow.

Deciduous trees shed their leaves at the end of the growing season. This prevents water loss through the large surface area of the leaves. Deciduous trees catch little snow in the winter. In southern Michigan we had an early snow before the leaves dropped and many limbs were broken from the weight of the snow. Leaves on deciduous trees are often damaged during the growing season by insects, fungi, animals, or wind. This annual replacement refurbishes the leaves. Some writers suggest that the bare branches at flowering time allow for better pollination especially for wind-pollinated species.

When deciduous trees start losing their leaves they reabsorb some of the nutrients from their leaves. Chlorophyll, the green color in the leaves, is one of the first chemicals to be broken down and absorbed. This is why tree leaves turn colors in the fall. In Michigan each group of trees normally has a distinct color. Ashes tend to be red-purple, Oaks yellow-brown, Aspens yellow, Sugar Maples orange-red, Silver Maples yellow, Red Maples red, Sassafras orange, and Hickories yellow. Color varies from season to season and exceptions to these general rules are common. However, with a little practice it is possible to locate particular tree species by their color.

Thanks to my friend Judith who suggested this blog post.

References

Conners, Deanna. (November 2017) Earthsky. https://earthsky.org/earth/why-do-trees-shed-their-leaves

Strieby, Sandra. (July 2013). Washington Native Plant Society Blog. https://www.wnps.org/blog/conifers-deciduous-trees

Panich, Justin. (No Date). Bioweb. http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/2010/panich_just/Site/Adaptations.html

Barnes, Burton V. and Warren H. Wagner Jr. (2004). Michigan Trees: A Guide to the Trees of the Great Lakes Region, Revised, Updated Edition

Copyright 2018 by Donald Drife

Webpage Michigan Nature Guy

Follow MichiganNatureGuy on Facebook