Sphaeropsis shoot blight

Last Fall, my friend Trapper Dave contacted me and asked what was killing the Jack Pine (Pinus banksiana) in a Kirtland’s Warbler planting near his cabin in Oscoda County. This planting was the subject of an earlier blog post. Needles on branches and entire trees suddenly turned brown. We checked other plantings and found dead trees several other places in Oscoda, Crawford, and Montmorency counties. Several of these stands were two year old Kirtland’s Warbler plantings and we became concerned about the impact this die-off might have on this endangered bird.

Trapper Dave contacted the DNR and a helpful Forest Health Technician replied that, “We have had several reports from roughly a four county area of this type of mortality. The pictures you sent are consistent with other pictures we have received from this area… I’ll be sure to send you a some more information once we are able to make a diagnosis.”

Later we received a report from the Diagnostic Services at Michigan State University. They identified Sphaeropsis canker (Sphaeropsis sp. or spp) as the cause of the die-off. From the limited sample, submitted by the Forest Technician, they could not identify which species it was or even if more than one species is involved. The genus is poorly understood and probably has many undescribed species.

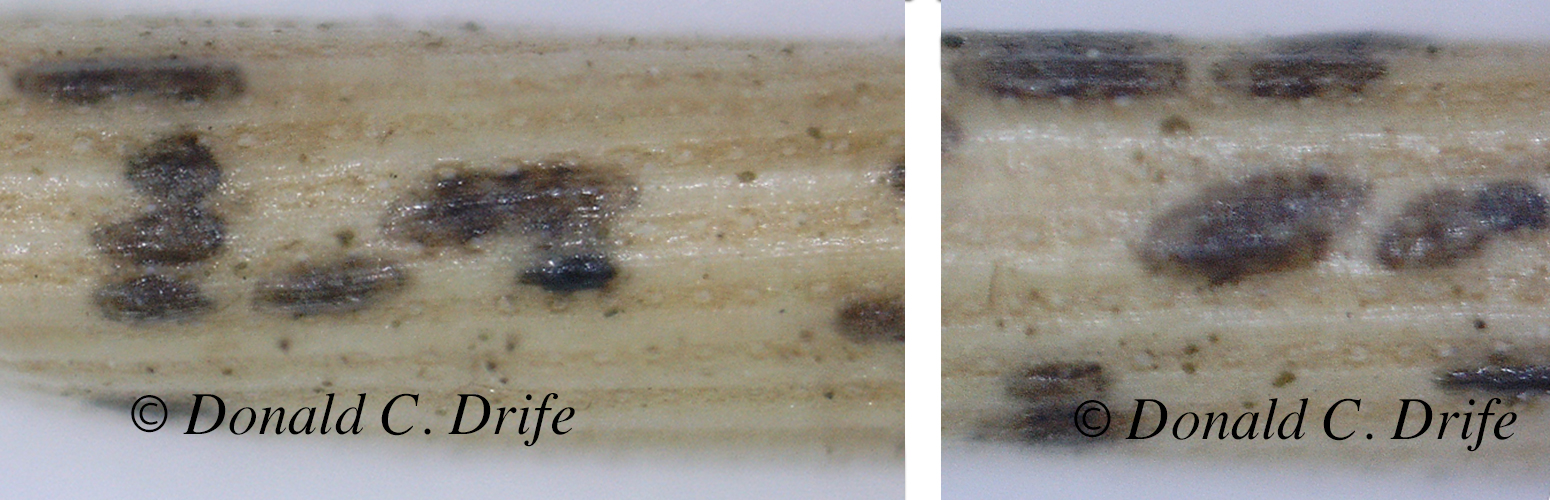

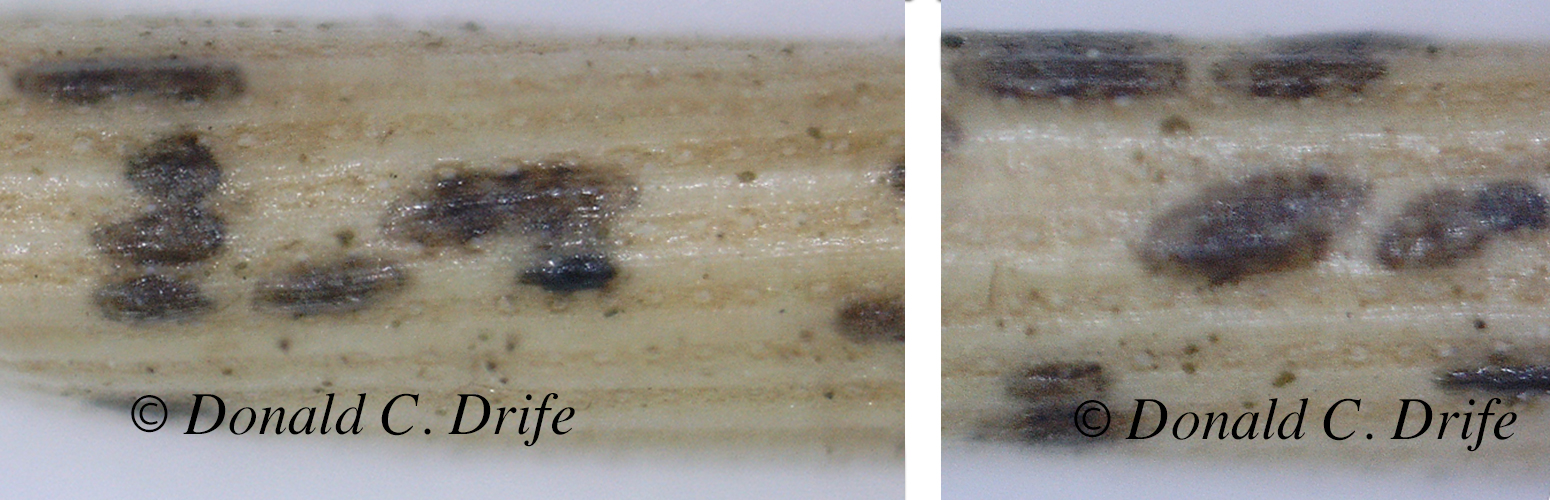

Jack Pine needles showing Sphaeropsis shoot blight

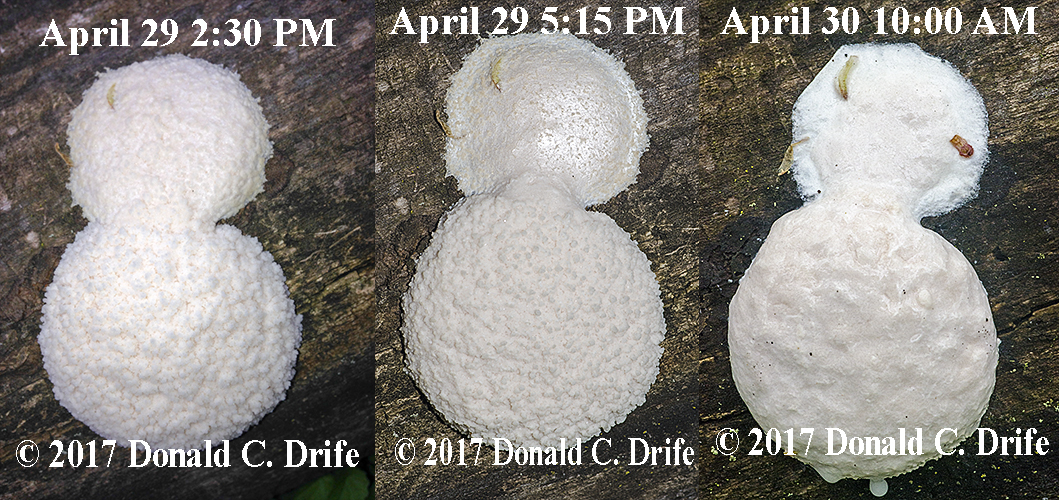

I looked up the fungus in Tree Maintenance (6th edition) by Pirone, Hartman, Sall, and Pirone. They list another newer generic name, Diplodia but use Sphaeropsis. They write that the fungus “overwinters in infected needles, twigs, and cones. In spring, the small fruiting bodies release egg-shaped, light brown spores… The fungus grows down through the needles and into the twigs, where it destroys tissues as far back as the first node.” (page 425).

Close-up of needle showing Sphaeropsis shoot blight spores

Several sources state that the spores overwinter in the cones but I could not find spores in the half-dozen cones I checked. The fungus kills the branches quickly. Die-off appeared over a two-week period but the trees must have been infected for most of the summer.

A USDA Northeastern Area Fact Sheet states, “Sphaeropsis shoot blight, formerly called Diplodia shoot blight, is worldwide in distribution and can infect many conifer hosts. Although many pine species are reported hosts, this disease causes severe damage only to trees that are predisposed by unfavorable environmental conditions. …Other predisposing environmental factors include poor site, drought, hail or snow damage, compacted soils, excessive shading, insect activity or other mechanical wounding. In the north-central United States, the most common hosts are Austrian, Scotch, mugo, red and jack pines grown in ornamental and windbreak plantings.”

We need to monitor the extent of the shoot blight damage in the Grayling area. It is a native fungus attacking a native tree that should have defense mechanisms. It was a dry year in the Grayling area so this may have made the trees more susceptible to infection. I am concerned that the USDA lists Jack Pine plantings, which of course is what we do for Kirtland’s Warbler, as being more susceptible to the infection. I did not find the fungus in the half dozen naturally occurring Jack Pine stands that I checked. If you find this fungus please report the location in the comments section of this blog post.

Copyright 2016 by Donald Drife

Webpage Michigan Nature Guy

Follow MichiganNatureGuy on Facebook